This site has now been archived (i.e. made read-only).

Please find my newer content at tinkerwithtech.net.

Photo by Arie Oldman on Unsplash

This site has now been archived (i.e. made read-only).

Please find my newer content at tinkerwithtech.net.

Photo by Arie Oldman on Unsplash

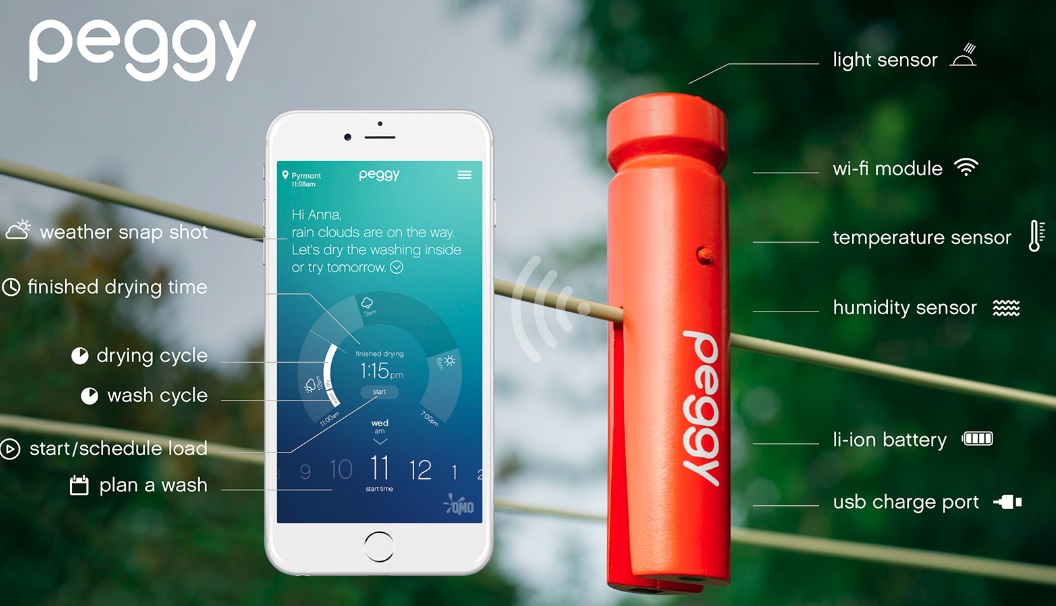

A frequently touted promise of IoT is to make your life easier by making everyday objects smarter. This has led to a slew of connected devices targeted at the consumer.

I don’t know about you, but many of these products seem to be targeting a need that I didn’t realise I had, rather than being genuinely useful.

Instead of developing yet another solution in search of a problem, I decided to address a very real need in our household. Due to busy schedules, I often find myself in the supermarket on the way home from work, trying to remember what food needs buying. It seems that I am not the only one experiencing this situation. Compounding this problem is that my teenage sons can consume a LOT, but what they are consuming at any point in time is erratic and difficult to predict.

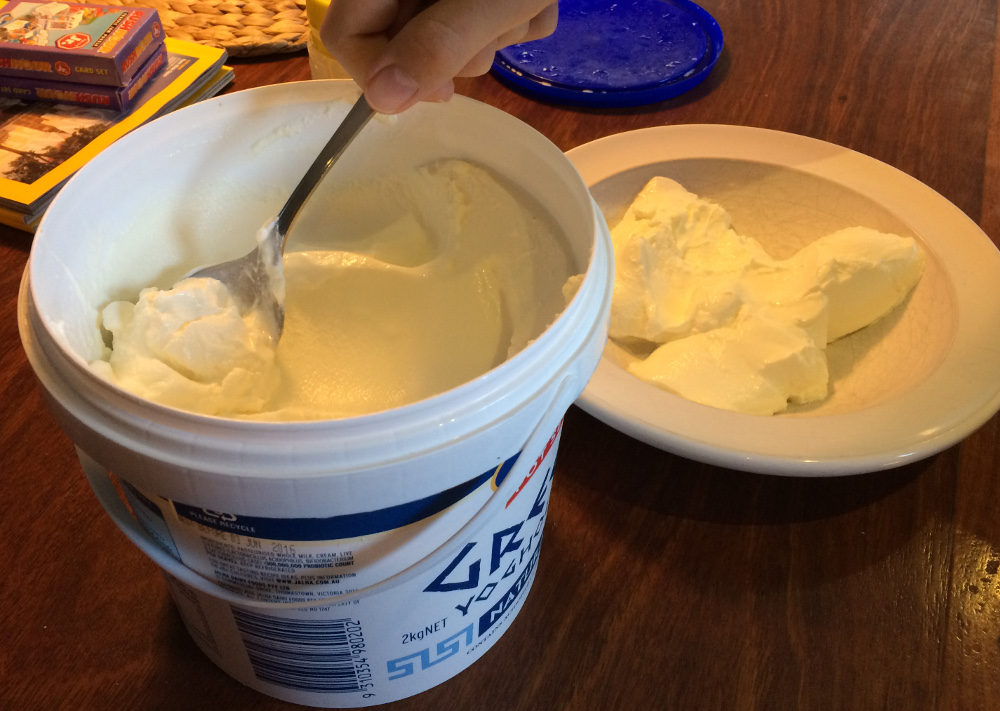

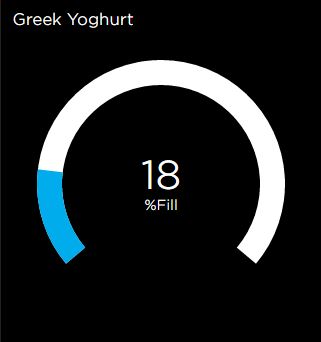

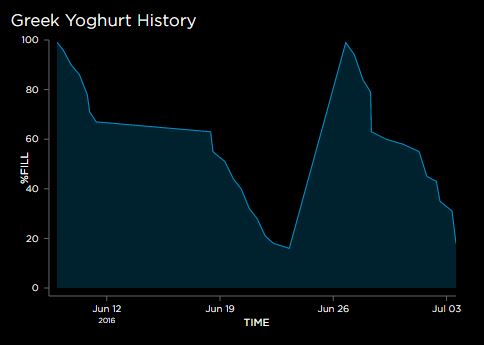

As an example, we recently went through a (relatively healthy) phase of consuming Greek yoghurt. To keep up with demand, we standardised on buying a 2kg (4.4lbs) tub – but only one tub at a time because of the space it occupies in the fridge. Unless I have recently eaten some, it becomes guesswork as to whether or not to replenish. And, in case you’re wondering, forget about getting my sons to proactively flag that anything is running out.

As an example, we recently went through a (relatively healthy) phase of consuming Greek yoghurt. To keep up with demand, we standardised on buying a 2kg (4.4lbs) tub – but only one tub at a time because of the space it occupies in the fridge. Unless I have recently eaten some, it becomes guesswork as to whether or not to replenish. And, in case you’re wondering, forget about getting my sons to proactively flag that anything is running out.

Time to hack together something to automatically give me that information, whenever and wherever I needed it. Yes, I could wait for a product (most likely at substantial cost) to be available like the smart mat demonstrated at CES 2016… but what would be the fun in that?

Time to hack together something to automatically give me that information, whenever and wherever I needed it. Yes, I could wait for a product (most likely at substantial cost) to be available like the smart mat demonstrated at CES 2016… but what would be the fun in that?

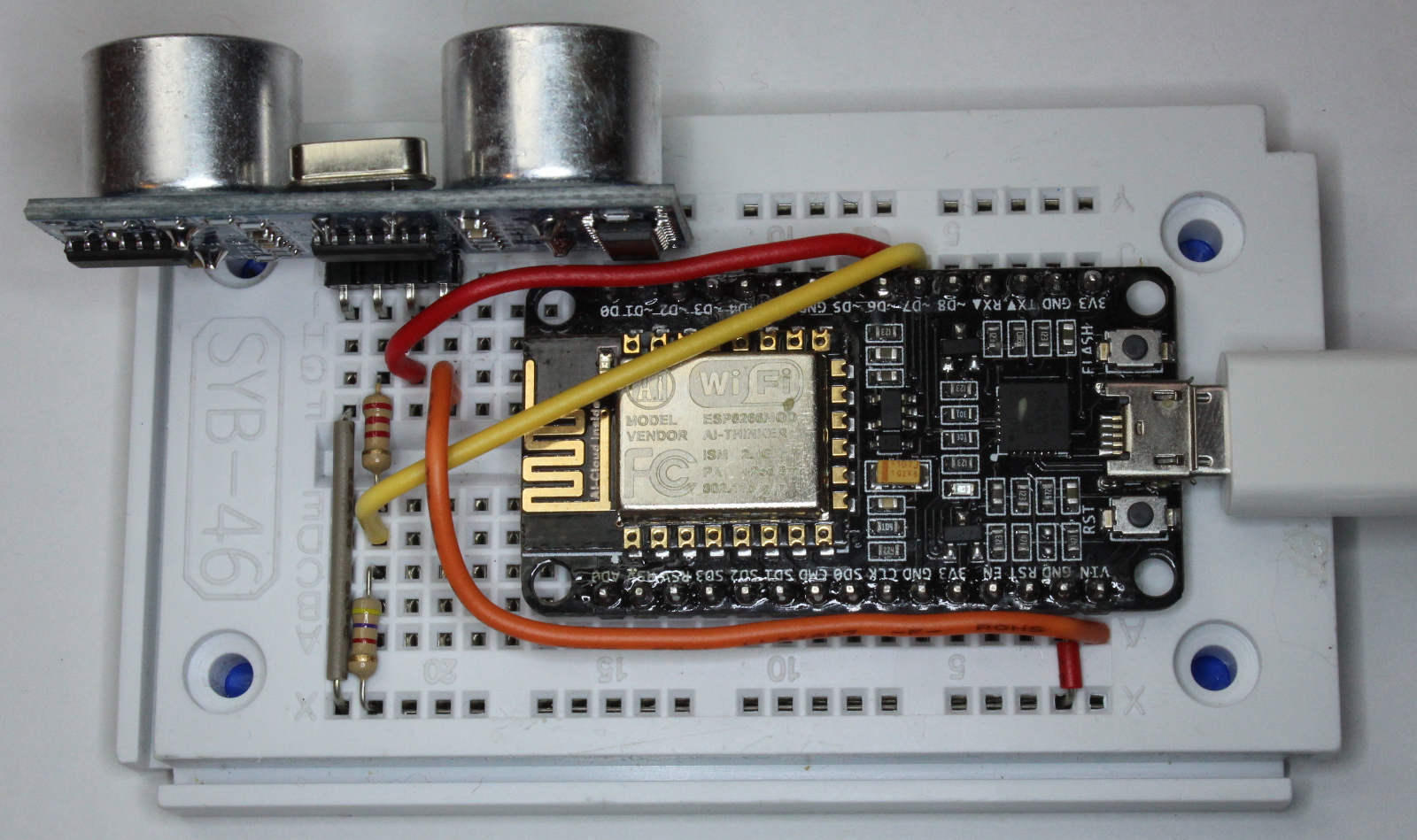

Fortunately, with a NodeMCU, some clever (at least I think so) Arduino code, the Adafruit IO cloud platform and a weight sensor, we have all the ingredients to build a device that will let us check the current yoghurt level on a smartphone at any time, and also send a text alert if supplies hit a critical level, all at a very low cost (excluding your time of course).

Fortunately, with a NodeMCU, some clever (at least I think so) Arduino code, the Adafruit IO cloud platform and a weight sensor, we have all the ingredients to build a device that will let us check the current yoghurt level on a smartphone at any time, and also send a text alert if supplies hit a critical level, all at a very low cost (excluding your time of course).

You can experience a live version of my yoghurt monitor here.

As you read on, keep in mind that this approach could be generalised to monitor any container. Also, the strategy would be to have multiple of these or similar devices. With many devices, it would be annoying to receive alerts every time something needs replenishing; instead, I imagine that they would update an automated shopping list, ready for when you are in the store.

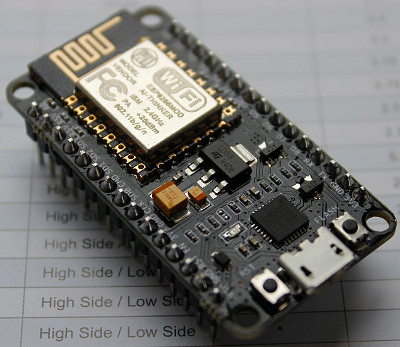

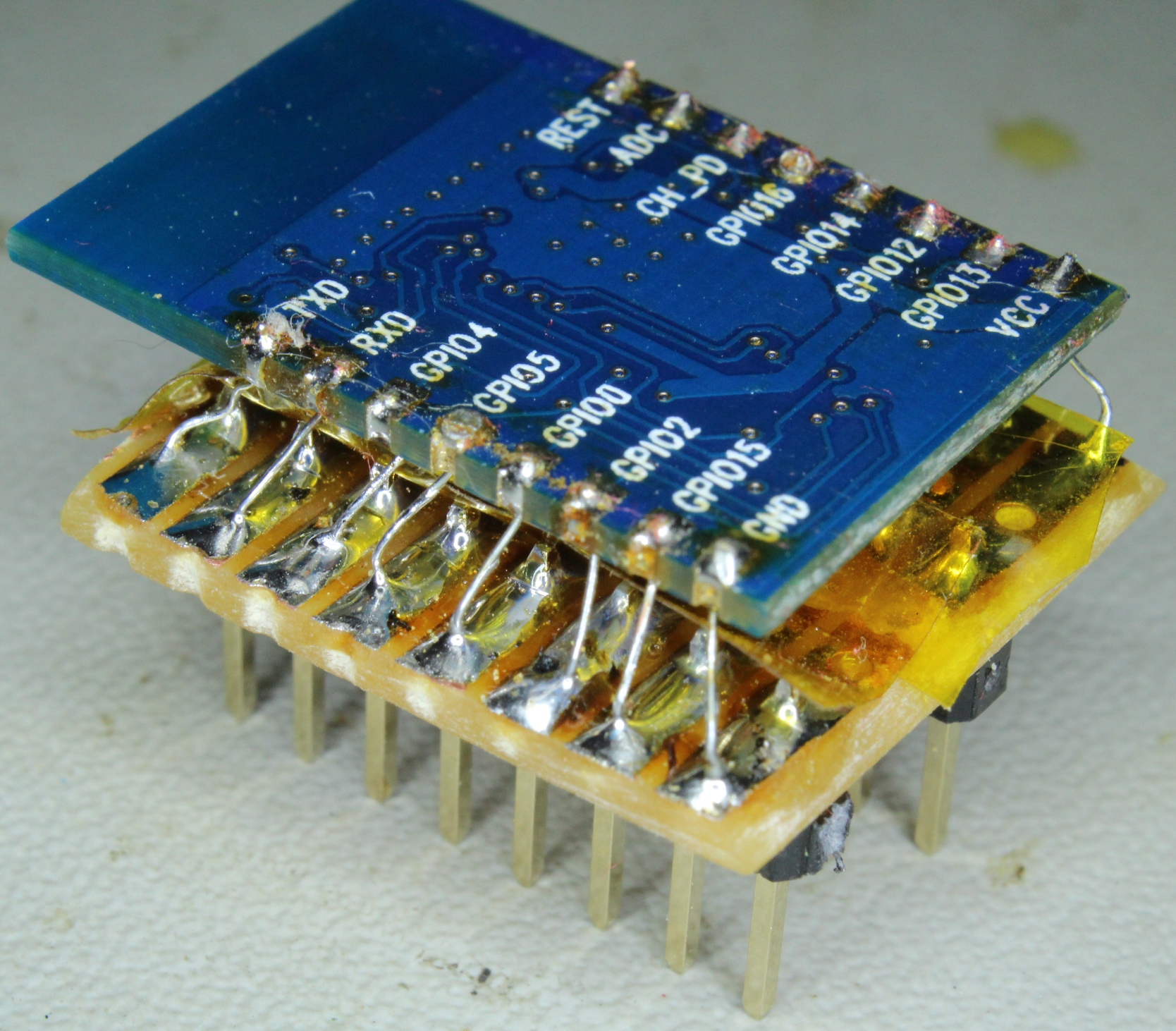

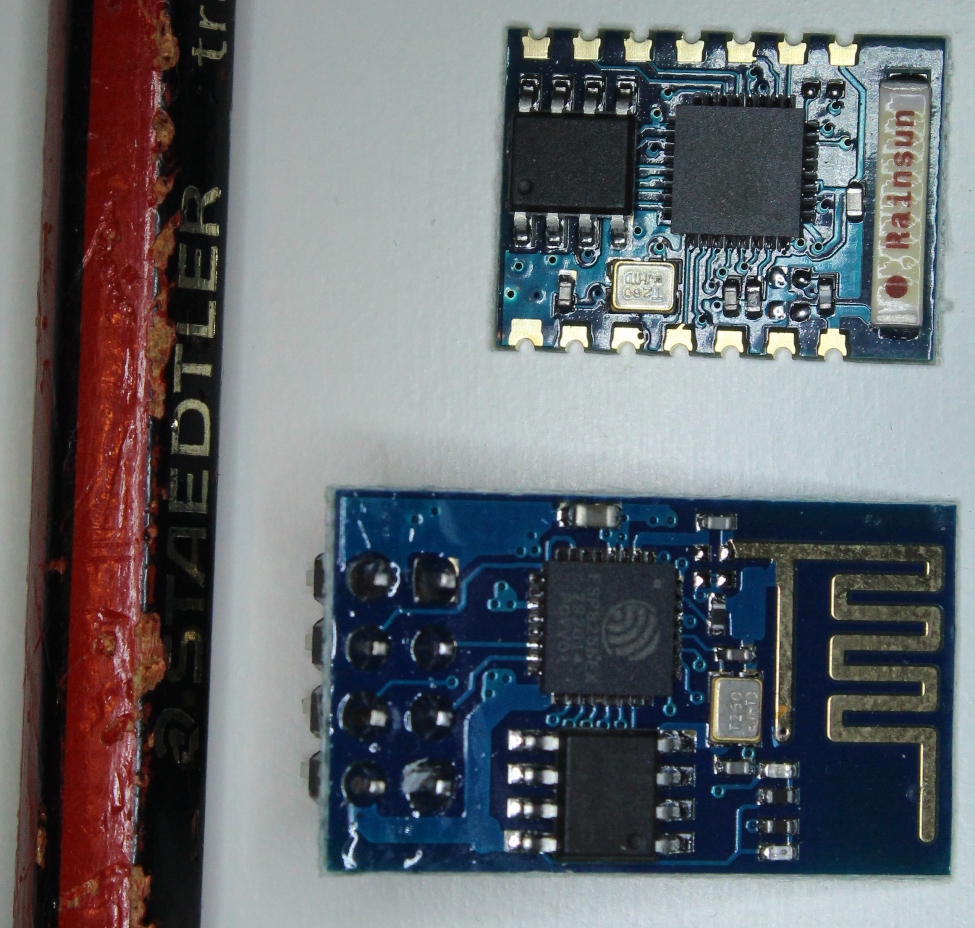

Over the last year I have standardised on the ESP8266 for all my small IoT projects. Its low price, ease of use (now that the Arduino IDE is available), tiny size and built in Wi-Fi makes it a compelling option.

Using Wi-Fi is a convenient way to link your newly created IoT device into your existing IT infrastructure – including cloud services – but it also has a drawback. Wi-Fi’s demand for power usually makes battery operation impractical for any real deployment. I have been able to get around this issue for most of my projects (e.g. the train and the smart shelf described on this blog) because they are for demonstration purposes only, requiring the battery to last no longer than a few hours.

Nevertheless, it is possible to put the ESP8266 into deep sleep and wake up periodically to check and activate Wi-Fi only when required. This would suit a scenario in which an IoT sensor sends relatively infrequent one way traffic (i.e. where real time control of the device is not needed). I wrote about the ESP8266 deep sleep option more than a year ago, but have not explored it any more until recently, when exactly such a project arose.

The other thing that I have done over the last year is to standardise on using the NodeMCU (hardware, not the LUA software). Especially when rolling out multiple small projects, it is immensely convenient to be able to plug a device into a USB port and just program it (automatically without having to wire up serial pins and then get the correct pins tied high / low for flashing / running). With no need to worry about providing 3.3V power, adding capacitors to prevent the ESP8266 power spikes from causing instability, or adding a resistor + cap for a power-on reset. No need to scale down the ADC input to 1V or to add my own test led… and all of this in a breadboard friendly package.

The other thing that I have done over the last year is to standardise on using the NodeMCU (hardware, not the LUA software). Especially when rolling out multiple small projects, it is immensely convenient to be able to plug a device into a USB port and just program it (automatically without having to wire up serial pins and then get the correct pins tied high / low for flashing / running). With no need to worry about providing 3.3V power, adding capacitors to prevent the ESP8266 power spikes from causing instability, or adding a resistor + cap for a power-on reset. No need to scale down the ADC input to 1V or to add my own test led… and all of this in a breadboard friendly package.

Also, just to be clear for those who may wish to follow along, I always use the “second generation” NodeMCU known as v2. The different versions are described here and I agree with that poster – i.e. don’t buy the v3 variant because its larger size means that it leaves no free breadboard holes on either side.

Unfortunately, with all this added convenience comes the drawback of added power consumption, which continues even when the ESP8266 is in deep sleep.

I measured 18mA to the NodeMCU board while the ESP8266 was in deep sleep mode – orders of magnitude more power hungry than I was looking for.

So for my iot-container project, I sought to retain the convenience of using the NodeMCU, but to address its power consumption shortcomings to allow battery operation.

Read further to hear what I did. Continue reading

In Part 1, I introduced the Smart Shelf concept, the sensor used, and the web page for displaying real-time updates.

Since then, I have also created a short video to demonstrate the project:

Part 1 explained how I used the Sparkfun ESP8266 Thing and the C SDK. For reliability reasons (in my case, when presenting / demonstrating in front of a live audience you ideally want things to work!), I have always preferred to use the C SDK, especially after the problems I experienced with Lua causing frequent reboots when I tried that approach a year ago.

But with the arrival earlier this year of the Arduino IDE, there is now a compelling alternative, which seems to work well (based on my limited experiments). So, as illustrated in this post, if you are an Arduino user, my view is that connecting a NodeMCU board and programming using the Arduino IDE is no more difficult than developing using an official Arduino board. The advantage is that you get built-in Wi-Fi, a smaller form factor and all this at a fraction of the cost. So for many applications, using an ESP8266 dev board like the NodeMCU might be the approach to consider first. Continue reading

But with the arrival earlier this year of the Arduino IDE, there is now a compelling alternative, which seems to work well (based on my limited experiments). So, as illustrated in this post, if you are an Arduino user, my view is that connecting a NodeMCU board and programming using the Arduino IDE is no more difficult than developing using an official Arduino board. The advantage is that you get built-in Wi-Fi, a smaller form factor and all this at a fraction of the cost. So for many applications, using an ESP8266 dev board like the NodeMCU might be the approach to consider first. Continue reading

Part 1 uses a Sparkfun ESP8266 Thing and the C SDK.

Part 1 uses a Sparkfun ESP8266 Thing and the C SDK.ESP8266 Dev Boards

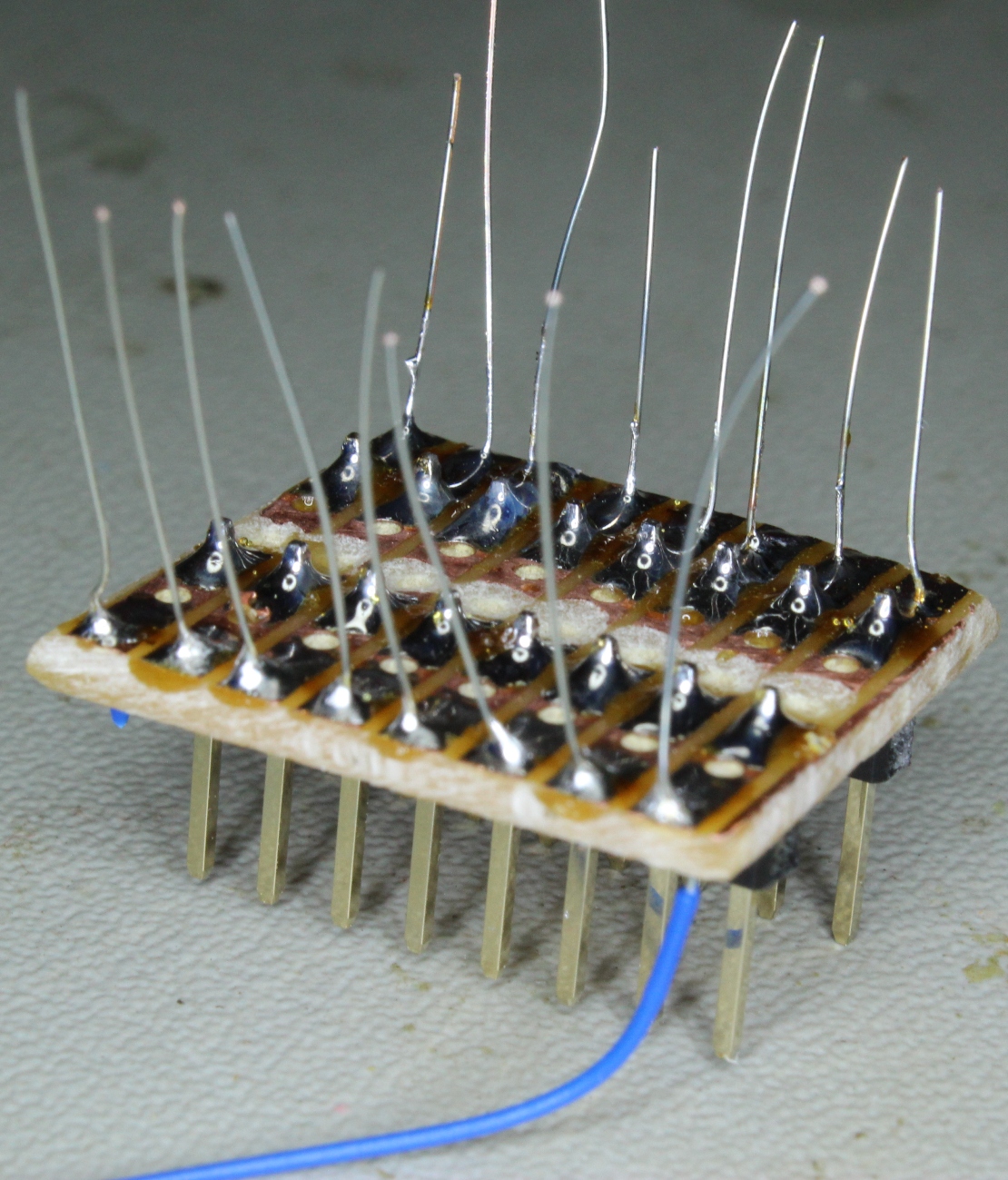

I have realised, after spending some time building small projects using the ESP-01, ESP-03 and ESP-12 modules running off battery power, that it can be quite time consuming and tedious to build the necessary power supply circuit and wire up serial connectors each time. Also, where space is not critical (unlike in my train project), it becomes quite compelling to consider dev boards that integrate an ESP8266, together with other features, in an-easy to use (bread-boardable) form factor.

This is even more the case if you look at the falling prices of, for example, the NodeMCU board on AliExpress, You are not likely to be able to build your own equivalent at a lower cost, even discounting the time it would take.

In my type of interactive projects (where the ESP8266 cannot be put into deep sleep for extended periods), operating off battery power realistically means using LiPo/LiIon. As a result, I found myself having to disconnect the battery, attach it to a LiPo charger and then reconnect for every charge cycle.

This is when I saw that the Sparkfun ESP8266 Thing “includes a LiPo charger, power supply, and all of the other supporting circuitry”. Very convenient for what I had in mind…

But before I get to that, I want to be clear that the Sparkfun ESP8266 Thing is actually not my favourite module for the following reasons:

It is worth noting that Sparkfun’s newer ESP8266 Thing – Dev Board fixes these issues (other than the price) – but then does not include a LiPo charger!

It would be interesting to find an inexpensive LiPo charger/management board that one could pair with a NodeMCU, if anyone knows of such a thing?

Smart Shelf Concept

I am intrigued by the notion put forward by David Rose (seen here presenting at TEDx) of “putting magic in the mundane – that is, having ordinary items that can do extraordinary things”.

I find compelling the notion that for everyday activities there will be a swing in popularity away from having to interact with complex abstract worlds behind glass screens toward a more “authentic” physical experience, for which we humans are so well adapted. But this shift will only be made possible by means of even more advanced technology – able to hide its own complexity.

This month the popular “Thomas the Tank Engine” toy celebrates its 70 anniversary. As a fun project, what could be more appropriate than to bring this traditional toy into the age of IoT, while preserving its physical appearance and simple charm?

For a short overview / teaser, watch the following video (be sure to select HD):

[youtube=https://youtu.be/-o6LYynn95E?hd=1&rel=0]

Inevitably there will be those who see this and ask “why?”

The short answer is that, as Hackaday believes, “why” is the wrong question.

A longer answer is that the train is simply BETTER when you can control its speed (remotely over wi-fi), more consistent to operate, especially at low speeds because of an auto “throttle-boost” that kicks in when the accelerometer senses that the train is going uphill, and more user-friendly with remote monitoring of the battery state.

And if you need still more justification, the Train appeared this week at a trade exhibition as a source of IoT data to demonstrate business software (go to YouTube here if you are interested, where one of my colleagues explains).

The main challenge was to be able to fit the required electronics into an existing form factor. As it transpired, the toy train was a lot more compact than I had anticipated. I had to undertake some delicate “surgery” to free up space underneath the train and behind the front face, but this was done in a way that a casual observer would not notice.

Follow the link to a full write-up to discover more of the details:

For a project that I have been working on (which is extremely space-constrained) I needed a second analog input – but the ESP8266 has only one. Whereas additional digital I/O lines can be accommodated quite easily using an external shift register to convert them into a serial stream, this is not as simple for analog signals.

For a project that I have been working on (which is extremely space-constrained) I needed a second analog input – but the ESP8266 has only one. Whereas additional digital I/O lines can be accommodated quite easily using an external shift register to convert them into a serial stream, this is not as simple for analog signals.

In specific situations you can get away with having only one ADC by multiplexing your sensors. In my scenario, because I was measuring totally unrelated things, this was not possible.

The most obvious approach is to add an external ADC. The drawback is that this requires you to get to grips with how to control your particular ADC chip, and beyond that to get serial communications working correctly. A further negative is that these ADCs usually require additional components in the form of stabilisation capacitors.

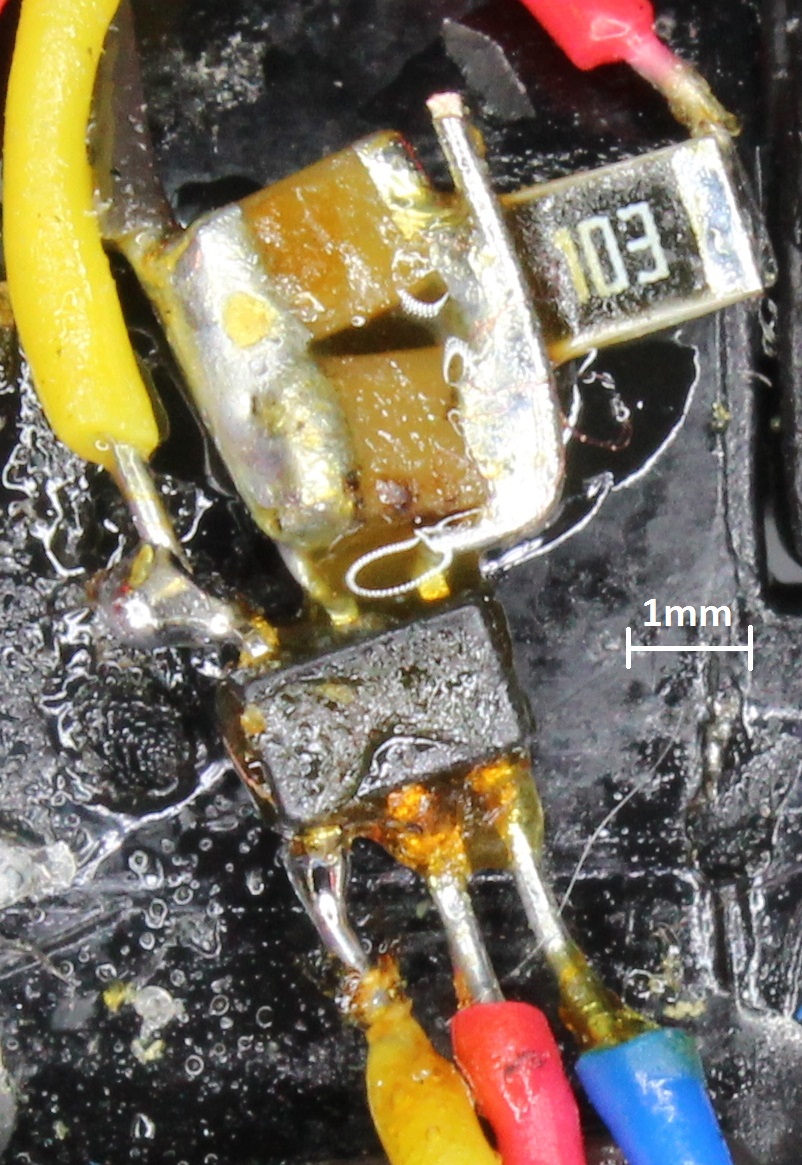

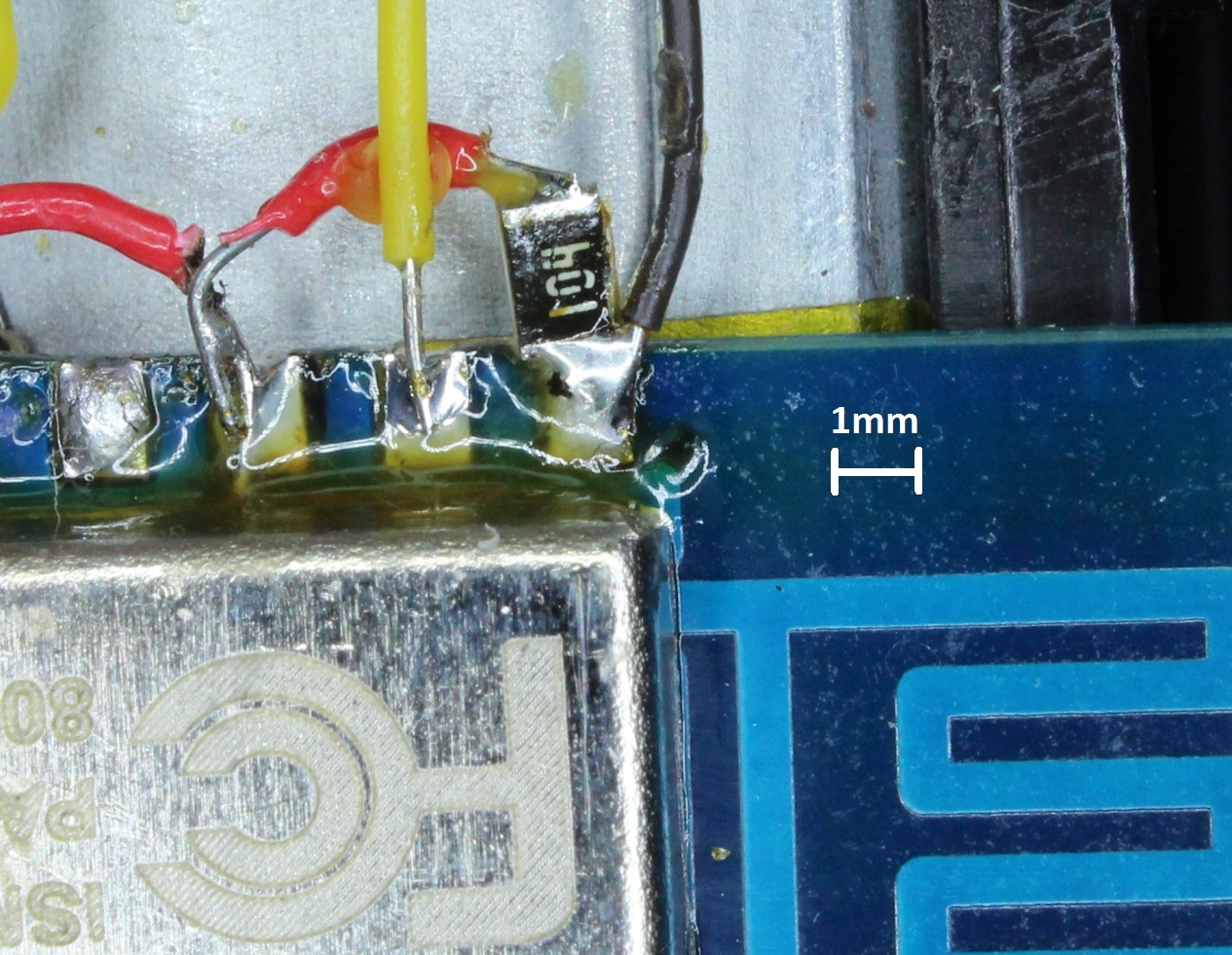

I therefore came up with a simpler alternative – using an analog switch ic. I was pleased to discover that they are now available in extremely small form factors. Actually, my choice turned out to be rather too small – at a size of 1 mm x 2 mm, soldering directly to each pin (without the benefit of pcb mounting) proved more of a challenge than I was looking for.

I therefore came up with a simpler alternative – using an analog switch ic. I was pleased to discover that they are now available in extremely small form factors. Actually, my choice turned out to be rather too small – at a size of 1 mm x 2 mm, soldering directly to each pin (without the benefit of pcb mounting) proved more of a challenge than I was looking for.

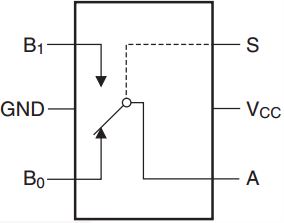

I settled on the FSA3157, which can operate off 3.3V and which allows you to select between 2 analog inputs using a single digital control output from the ESP8266. You are then able to feed that selected analog input to the single ADC input on the ESP8266. Further good news is that they cost well under a dollar each. Continue reading

I settled on the FSA3157, which can operate off 3.3V and which allows you to select between 2 analog inputs using a single digital control output from the ESP8266. You are then able to feed that selected analog input to the single ADC input on the ESP8266. Further good news is that they cost well under a dollar each. Continue reading

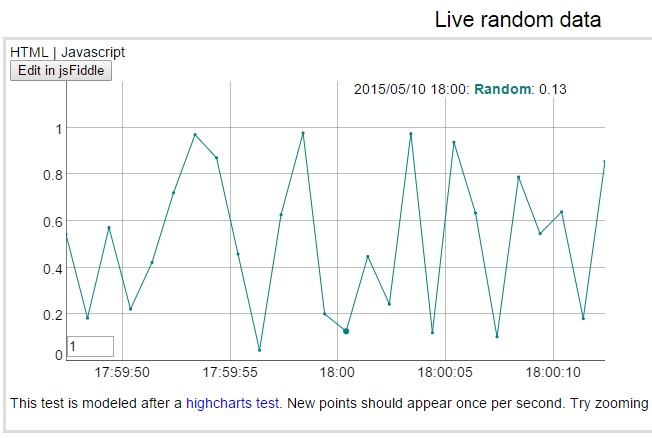

Recently, I have been using MQTT to stream ESP8266 sensor data to a Mosquitto broker running on a Raspberry Pi. I wanted to develop something to show the stream graphically.

I have previously found Dygraphs to be a great piece of software. I like the way it consists purely of client-side javascript, which runs entirely within a web browser. In fact, you can even open an HTML file (containing javascript) from your local disk, without requiring a web server.

I specifically wanted to build something along the lines of Dygraph’s dynamic update demo, except that I wanted a constant scrolling “window” of values – like a heart monitor for example. (Really, what is the use of having all your data scrunch up against the left of the window?).

I specifically wanted to build something along the lines of Dygraph’s dynamic update demo, except that I wanted a constant scrolling “window” of values – like a heart monitor for example. (Really, what is the use of having all your data scrunch up against the left of the window?).

Having solved that issue, I then had to connect the graph to my MQTT broker to be able to receive live data to display.

This post goes into details of how I did this, but before going further, here is the result:

[wpvideo uIHfHtPH]

A lot of the initial interest in the ESP8266 has been about using it as an add-on wifi board together with something like an Arduino. Now, in many situations this makes sense: leverage your skills and familiarity with your chosen MCU and its development environment, but add Wi-Fi capabilities using the ESP8266 simply and cheaply.

But what interests me more is what becomes possible when using the ESP8266 as a single solution for both processing and Wi-Fi. Nowhere is this more relevant than when size is a primary constraint. This is true of most wearable devices, but can often be the case for Internet of things (IoT) devices – particularly those that were never originally designed to be IoT enabled.

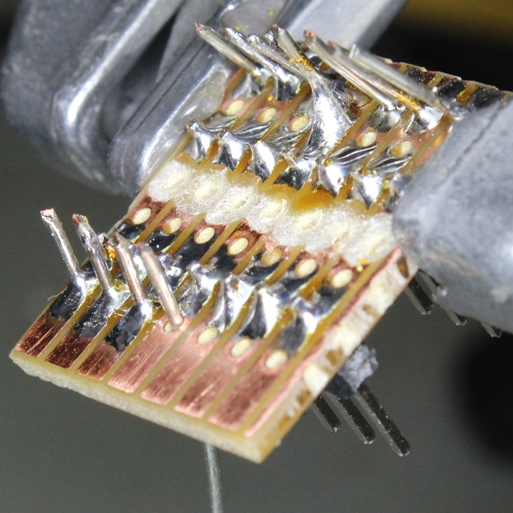

In this realm, it quickly becomes crystal clear that SMD technology is not just an option, but a prerequisite. Without it, even a very few discrete components demand more space than an entire ESP8266 board.

Unfortunately these tiny components are more difficult to work with than discretes, and generally a PCB is desirable to mount the components. However, I am finding that with magnification, flux and some patience, it is possible to build space-constrained prototype circuits on the fly.

I will be posting a new project in

I will be posting a new project in 3 weeks May that is a good demonstration of this, but for now here are a few glimpses to illustrate.

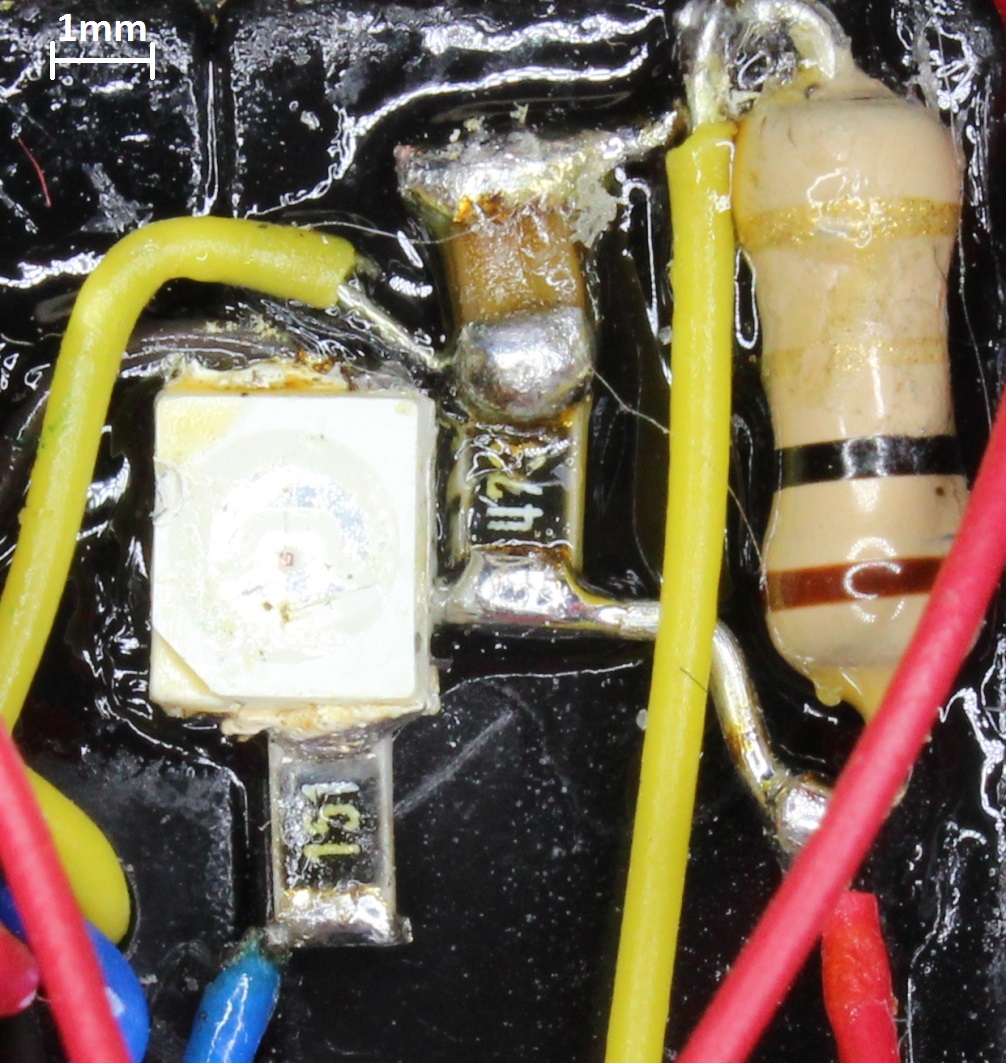

The first example is adding a 100nF capacitor as part of a start-up reset circuit. Here I have soldered an SMD part directly to the ESP-12 board reset pin. I was using an 0805 part, which at 1mm x 2mm takes up almost no additional space.

My second example is a circuit for measuring current. A discrete 1/4 watt resistor was used because of the requirement to carry the full current in series with the load. But, for my purposes, I wanted to smooth out the resultant noisy PWM-driven signal. So I used a low pass filter consisting of an SMD capacitor and resistor before sending on to the ADC of the ESP8266.

Also in the picture is an SMD led and current limiting resistor, surrounded by epoxy holding everything together.

There simply would not have been space for using the discrete equivalents.

(Looking at these magnified views, I really need to try and clean off all that flux residue…!)

Over the last couple of weeks I have been sidetracked by another project – about which I’ll certainly share more details when it is done. The project has a requirement to stream readings to the Internet from an accelerometer (in a very small form factor), so I decided to pair one with an ESP8266.

As I work more with the ESP8266, I am finding a common theme when using this chip.

As I work more with the ESP8266, I am finding a common theme when using this chip.

On the one hand its low cost and extreme functionality in a very small package makes it a real game changer, and I was glad to see an article in Hackaday a week or so ago bringing this message to a wider audience. Essentially, the ESP8266 is not much more difficult to program than an Arduino, yet gives you a tiny, single-MCU solution with Wi-Fi included.

BUT, on the other hand, it can be really difficult to find good, clear information – at which point it suddenly becomes NOT an easy task to get something done. Although this situation is changing, it currently costs me more hours than I would have imagined to accomplish certain tasks.

I found myself in this wilderness recently after selecting the ADXL345 accelerometer chip, which I chose mainly because it works off 3.3V and because it has a good reputation. It also supports both SPI and I2C, which gives greater flexibility when interfacing to an MCU. So far, so good.

This blog post details the different approaches I tried, and the challenges I faced. These were:

This blog post details the different approaches I tried, and the challenges I faced. These were:

At the end I include a video showing a working ESP8266 (ESP-12 version, because I will later need an ADC) streaming accelerometer readings to an MQTT broker running on a Raspberry Pi, with results shown graphically on a PC, which is connecting to that broker.

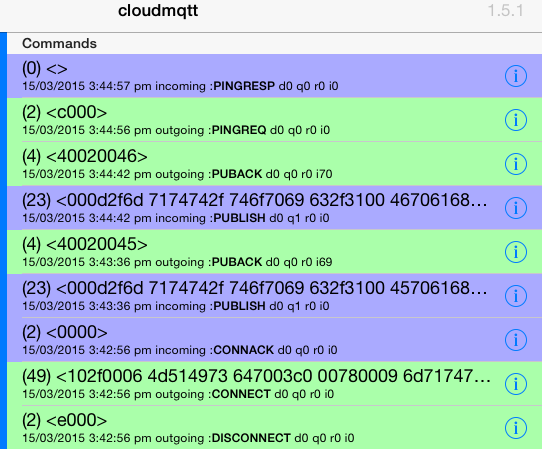

One of the most important reasons that I considered using MQTT for my haptic wristband project was because of its ability to handle devices that are intermittently connected. IOT devices, even if nominally switched on, may at any given time be unavailable due to sleep modes (even although this direction did not prove as promising on the ESP8266 for my application as I’d initially hoped), or simply because the device has temporarily lost Wi-Fi connectivity.

Whatever the cause of disruption, the MQTT architecture provides for the broker to store any important messages (i.e. those flagged with high qos or “quality of service”) to be later delivered to a client that had been previously subscribed, also with high qos, but is at that point in time disconnected.

Whatever the cause of disruption, the MQTT architecture provides for the broker to store any important messages (i.e. those flagged with high qos or “quality of service”) to be later delivered to a client that had been previously subscribed, also with high qos, but is at that point in time disconnected.

For my project this is crucial. I have always envisaged my wristband to be an additional “priority” channel to cut through the barrier of noise created by the visual overload of our multiple screens, through the beeps and buzzes representing emails, meeting requests, tweets, texts, phone calls and missed calls – which are themselves competing for (hopefully) the majority of your attention directed at real people and real objects around you as you do your job and live your life!

Therefore, as a device that handles relatively few but very important notifications, a missed message is unacceptable.

Unfortunately, as I hinted at last week, I struggled to get this MQTT mechanism to work. The main problem I was having was that I was not sure where the fault lay – and even wondered if I was misunderstanding the way that MQTT should work. I began to suspect that the free MQTT broker that I was using did not support this more advanced behaviour. As it transpired, and thanks to some timely help from Carl at CloudMQTT support, the MQTT broker turned out to be fine – it was both the ESP8266 client and the MQTT test software that I was using that were dropping the ball.

After wading through many documents on the web, I also realised that this whole area of MQTT persistence is quite confusing and not well explained from the point of view of someone actually wanting to make use of it. So, in this post, I aim to first explain how persistence should work, and then afterwards provide all the details for someone to actually try it out for themselves. Along the way I also discover a couple of great new products. Continue reading

[Update May 2016: for reducing power consumption of a NodeMCU board, see this post where I revisit the topic].

In my previous post, I mentioned that one of the reasons that I was excited about MQTT was because of its potential to allow power savings schemes on the ESP8266. The MQTT broker could asynchronously hold messages during the period that the ESP8266 was in a sleep cycle, to ensure that nothing is missed while dramatically reducing average power consumption.

This week I have hit a few obstacles, mainly due to the immaturity of current implementations of some of the latest MQTT qos (quality of service) features – at least that is what I suspect at this point. But more on that next week.

So, focusing on the ESP8266: my initial research had led me to believe that “deep sleep” mode was the way to go. Who can argue with using just 78μA during deep sleep?

To be able to implement deep sleep (without adding extra hardware to generate a wake-up signal), you need to link 2 pins on the ESP8266, as discussed here. Fortunately, the ESP-03 module has pads broken out on the PCB that you can join together. By linking these, you lose the ability to use GPIO16, but gain an automatic wake-up from deep sleep after the number of microseconds that you specify in the system_deep_sleep(time_in_us) call. You can understand better how this works by looking at the ESP-03 schematic.

To avoid any confusion, the pads to join are shown below:

I have recently had a rethink about how I will link my wristband to an alert source.

To demo my first prototype, I hosted a web page on the ESP8266 device itself. Selecting a button on the web page posted a value, which activated the chosen vibration pattern. This is a very convenient way to demo the concept, but, in the real world it has some significant drawbacks.

The first drawback is that the whole submit / refresh cycle of a web page is not particularly fast, which also probably means that the web server on the ESP8266 is having to do a relatively large amount of work. I therefore had originally planned to eliminate some of this overhead by following the approach in the ESP8266 IoT example of using http methods and json, which can be called from anything (e.g. from another pc/server by using the curl command).

But this does not solve a second issue, which is that the ESP8266 server has to be “always on”, waiting for a command from the remote web page. This is likely to make power savings measures (sleep cycles) difficult, which is less than ideal given that Wi-Fi is not as power efficient as Bluetooth – notwithstanding that Wi-Fi continues to evolve.

The third problem is the direction of the link. To communicate with the wristband requires that you initiate a connection. This is not a problem if you are on the same network (and also assuming you always know the ip address of the wristband). However, if the source of the alert is from outside the network, a firewall port will need to be opened and forwarded – something that will usually be out of the question on most corporate networks.

With this background, and inspired by Peter Scargill’s exploits, I decided to investigate MQTT. Potentially if offered to solve all three of my issues:

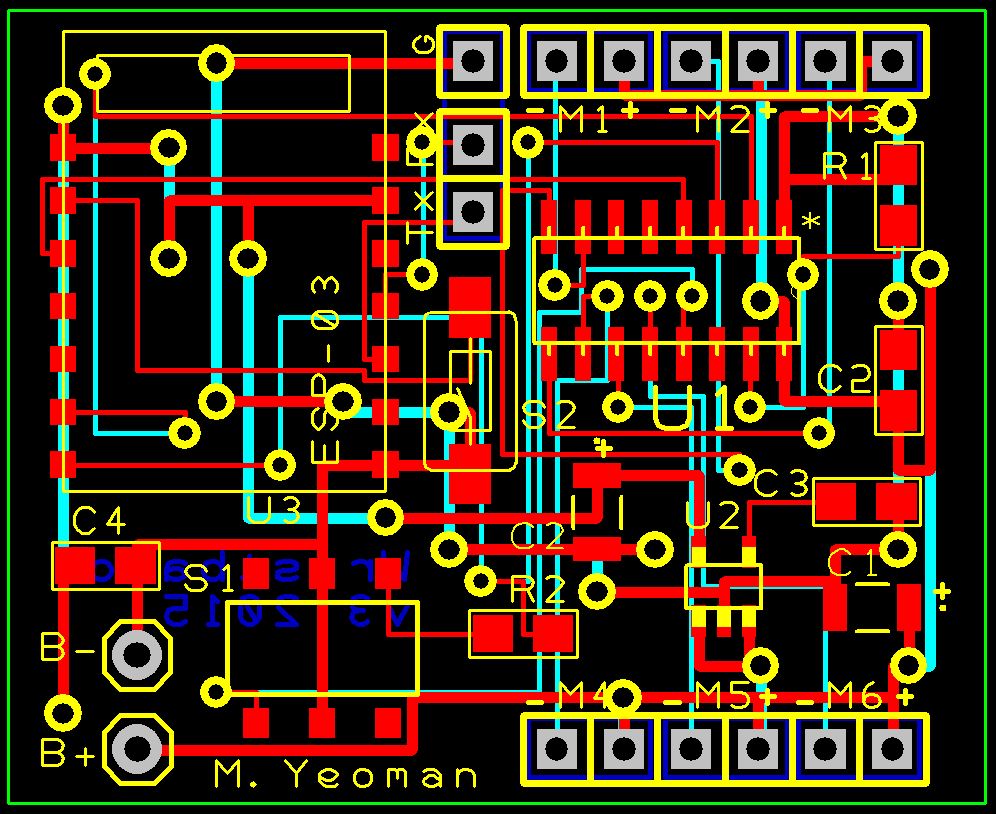

These days I use DesignSpark PCB for designing my PCBs. A few years ago, I judged it to be the best of the free software after trying Eagle, Kicad and others – and I like the way that RS is continuously developing it. Ultimately though, whatever CAD tool you choose, the most important thing is to become familiar with it.

I used DesignSpark to generate a PCB for my vibrating wristband from the schematic that I had already captured. I manually positioned the components, but let the auto-router route all the tracks. I had to move the components slightly over a few iterations to get the auto-router to be able to complete all the nets.  I have previously had two sets of PCBs made at ITEAD Studio, and been very happy with the results. Certainly their prices are good at $1 per 5cmx5cm board.

I have previously had two sets of PCBs made at ITEAD Studio, and been very happy with the results. Certainly their prices are good at $1 per 5cmx5cm board.

Just be aware of minimum sizes in your design. In the past I have specified silkscreen text and lines that were too small to be printed. It is very easy to lose touch of just how small things really are when you are looking at a full screen CAD view. ITead has posted guidelines here, but basically you should be fine if you don’t need to go below 0.2 mm.

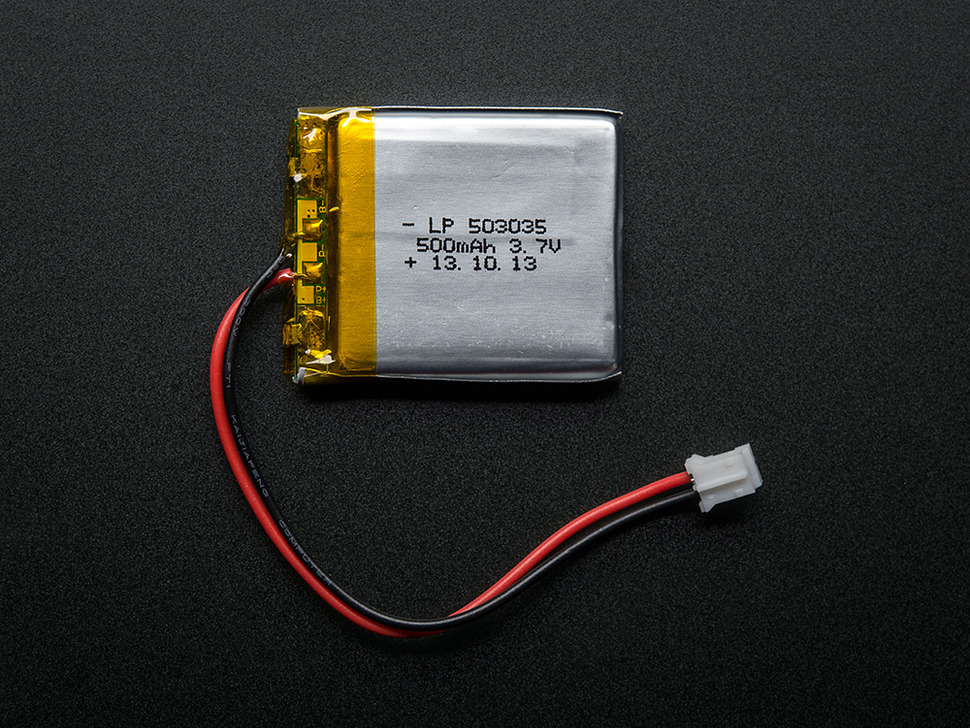

I designed the board with exactly the same dimensions as the Adafruit battery that I plan to use, since the board will sit on top of this battery (37mm x 30mm). The process for generating the correct files for an ITEAD Studio 2-layer board is quite simple, but you should follow the following steps once you have finished your design: Continue reading

I designed the board with exactly the same dimensions as the Adafruit battery that I plan to use, since the board will sit on top of this battery (37mm x 30mm). The process for generating the correct files for an ITEAD Studio 2-layer board is quite simple, but you should follow the following steps once you have finished your design: Continue reading

It was fantastic to see my vibrating wristband appear on http://hackaday.com/2015/02/12/a-haptic-bracelet-for-physical-computing/

Brian Benchoff did a great job writing his article.

Meanwhile, I am working on my next prototype. The main goals are to:

I have managed to get a newly arrived ESP-03 working on a breadboard, including properly latching the shift register during updates, as I mentioned I intended to do.

With the previous ESP-01 version, I tried making an adapter to reuse the ESP8266, but it all went wrong when the solder flowed more than I intended. It then struck me that the modules are so cheap that it is not worth going to all the effort – just keep one permanently for breadboard prototyping.

I have been making extensive use of the SDK examples to work out what to do. But, when faced with a bunch of c modules and headers for the first time, it can be difficult to get an overview of how they interconnect and interrelate.

There must surely exist some good (and free) tools to generate these “call graphs“. After all, this capability is built into any compiler?